There are two parts to dbplyr SQL translation: translating dplyr

verbs, and translating expressions within those verbs. This vignette

describes how individual expressions (function calls) are translated;

vignette("translation-verb") describes how entire verbs are

translated.

Getting started with translations

In this vignette, I’ll use lazy_frame() to create a toy

lazy table that allows us to see the translation without needing to

connect to a real database:

lf <- lazy_frame(x = 1, y = 2, g = "a")

lf |> mutate(z = (x + y) / 2)

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *, ("x" + "y") / 2.0 AS "z"

#> FROM "df"The default lazy_frame() uses a generic database that

generates (approximately) SQL-92 compliant SQL. You can use

simulate_*() connections to see the translations used by

different backends. Different databases generate slightly different SQL;

see vignette("new-backend") for more details.

lf_sqlite <- lazy_frame(x = 1, con = simulate_sqlite())

lf_access <- lazy_frame(x = 1, con = simulate_access())

lf_sqlite |> transmute(z = x^2)

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT POWER(`x`, 2.0) AS `z`

#> FROM `df`

lf_access |> transmute(z = x^2)

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT "x" ^ 2.0 AS "z"

#> FROM "df"One key difference between dbplyr-generated SQL and hand-written SQL

is that dbplyr always quotes all table and column names. This is verbose

but necessary because column names in database tables can be any string,

including SQL reserved words like select or

if. Quoting all names ensures that dbplyr-generated SQL

always works regardless of the table and column names involved.

In general, perfect translation is not possible because databases

don’t have all the functions that R does. The goal of dbplyr is to

provide a semantic rather than a literal translation: what you mean,

rather than precisely what is done. In fact, even for functions that

exist both in databases and in R, you shouldn’t expect results to be

identical; database programmers have different priorities than R core

programmers. For example, in R in order to get a higher level of

numerical accuracy, mean() loops through the data twice.

R’s mean() also provides a trim option for

computing trimmed means; this is something that databases do not

provide.

If you’re interested in how translate_sql() is

implemented, the basic techniques that underlie the implementation of

translate_sql() are described in “Advanced R”.

Basic differences

There are two fundamental differences between R and SQL:

-

"and'mean different things. R can use either"or'for strings, but in ANSI SQL, must be"used for names and must be'used for strings.lf |> filter(x == "x") #> <SQL> #> SELECT * #> FROM "df" #> WHERE ("x" = 'x') -

R and SQL have different defaults for integers and reals. In R, 1 is a real, and 1L is an integer. In SQL, 1 is an integer, and 1.0 is a real.

Known functions

Modulo arithmetic

dbplyr translates %% to the SQL equivalents but note

that it’s not precisely the same: most databases use truncated division

where the modulo operator takes the sign of the dividend, where R using

the mathematically preferred floored division with the modulo sign

taking the sign of the divisor.

df <- tibble(

x = c(10L, 10L, -10L, -10L),

y = c(3L, -3L, 3L, -3L)

)

db <- copy_to(memdb(), df)

df |> mutate(x %% y)

#> # A tibble: 4 × 3

#> x y `x%%y`

#> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 10 3 1

#> 2 10 -3 -2

#> 3 -10 3 2

#> 4 -10 -3 -1

db |> mutate(x %% y)

#> # A query: ?? x 3

#> # Database: sqlite 3.51.2 [:memory:]

#> x y `x%%y`

#> <int> <int> <int>

#> 1 10 3 1

#> 2 10 -3 1

#> 3 -10 3 -1

#> 4 -10 -3 -1dbplyr no longer translates %/% because there’s no

robust cross-database translation available.

Bitwise operations

bitwNot(), bitwAnd(),

bitwOr(), bitwXor(),

bitwShiftL(), and bitwShiftR() are all

supported:

lf |> transmute(x = bitwAnd(x, 3L), y = bitwShiftL(x, 2L))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT "x", "x" << 2 AS "y"

#> FROM (

#> SELECT "x" & 3 AS "x", "y", "g"

#> FROM "df"

#> ) AS "q01"Type coercion

Type coercion functions use the corresponding SQL CAST()

call:

lf |> transmute(x = as.integer(y), y = as.character(x))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT "x", CAST("x" AS TEXT) AS "y"

#> FROM (

#> SELECT CAST("y" AS INTEGER) AS "x", "y", "g"

#> FROM "df"

#> ) AS "q01"- integer types:

as.integer(),as.integer64() - floating point:

as.numeric(),as.double() - character:

as.character() - logical:

as.logical() - date/time:

as.Date(),as.POSIXct()

For database-specific types not covered by these functions, use

as():

NULL/NA handling

-

is.na(),is.null(): test forNULL. -

na_if(): replace a value withNULL. -

coalesce(): replaceNULLwith a default value.

Aggregation

All databases provide translation for the basic aggregations:

mean(), sum(), min(),

max(). Databases automatically drop NULLs (their equivalent

of missing values) whereas in R you have to ask nicely. The aggregation

functions warn you about this important difference:

lf |> summarise(z = mean(x))

#> Warning: Missing values are always removed in SQL aggregation functions.

#> Use `na.rm = TRUE` to silence this warning

#> This warning is displayed once every 8 hours.

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT AVG("x") AS "z"

#> FROM "df"

lf |> summarise(z = mean(x, na.rm = TRUE))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT AVG("x") AS "z"

#> FROM "df"Note that aggregation functions used inside mutate() or

filter() generate a window translation:

lf |> mutate(z = mean(x, na.rm = TRUE))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *, AVG("x") OVER () AS "z"

#> FROM "df"

lf |> filter(mean(x, na.rm = TRUE) > 0)

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT "x", "y", "g"

#> FROM (

#> SELECT *, AVG("x") OVER () AS "col01"

#> FROM "df"

#> ) AS "q01"

#> WHERE ("col01" > 0.0)Most backends also support:

-

sd(),var(),cor(),cov() -

median(),quantile() -

n(),n_distinct() -

all(),any() str_flatten()

Conditional evaluation

if, ifelse(), and if_else()

are translated to CASE WHEN:

lf |> transmute(z = ifelse(x > 5, "big", "small"))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT CASE WHEN ("x" > 5.0) THEN 'big' WHEN NOT ("x" > 5.0) THEN 'small' END AS "z"

#> FROM "df"case_when(), case_match(), and

switch() are also supported:

lf |>

mutate(z = case_when(

x > 10 ~ "medium",

x > 30 ~ "big",

.default = "small"

))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT

#> *,

#> CASE

#> WHEN ("x" > 10.0) THEN 'medium'

#> WHEN ("x" > 30.0) THEN 'big'

#> ELSE 'small'

#> END AS "z"

#> FROM "df"

lf |> mutate(z = switch(g, a = 1L, b = 2L, 3L))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *, CASE "g" WHEN ('a') THEN (1) WHEN ('b') THEN (2) ELSE (3) END AS "z"

#> FROM "df"String functions

Base R string functions and their stringr equivalents are widely supported:

-

nchar(),str_length() -

tolower(),toupper(),str_to_lower(),str_to_upper(),str_to_title() -

trimws(),str_trim() -

paste(),paste0(),str_c() -

substr(),substring(),str_sub()

lf |> transmute(x = paste0(g, " dog"))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT CONCAT_WS('', "g", ' dog') AS "x"

#> FROM "df"

lf |> transmute(x = substr(g, 1L, 2L))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT SUBSTR("g", 1, 2) AS "x"

#> FROM "df"Many backends also support regular expression functions like

str_detect(), str_replace(),

str_replace_all(), str_remove(),

str_remove_all(), str_squish(), and

str_like(). Support varies by backend; see the individual

backend documentation for details.

Date/time functions

dbplyr supports many lubridate functions for extracting date components:

-

today(),now() -

year(),month(),day(),mday(),hour(),minute(),second()

lf_dt <- lazy_frame(dt = Sys.time())

lf_dt |> transmute(

year = year(dt),

month = month(dt),

day = day(dt)

)

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT

#> EXTRACT(year FROM "dt") AS "year",

#> EXTRACT(month FROM "dt") AS "month",

#> EXTRACT(day FROM "dt") AS "day"

#> FROM "df"Some backends also support additional lubridate functions including

yday(), wday(), week(),

isoweek(), quarter(), isoyear(),

floor_date(), and period functions like

seconds(), minutes(), hours(),

days(), weeks(), months(),

years().

Several backends (including PostgreSQL, Snowflake, SQL Server, Redshift, and Spark SQL) support clock functions for date arithmetic.

-

add_days(),add_years() date_build()-

get_year(),get_month(),get_day() date_count_between()difftime()

clock functions tend to be easier to translate than lubridate functions because they are more specific.

Unknown functions

Any function that dbplyr doesn’t know how to convert is left as is. This means that database functions that are not covered by dbplyr can often be used directly.

Prefix functions

Any function that dbplyr doesn’t know about will be left as is:

lf |> mutate(z = foofify(x, y))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *, foofify("x", "y") AS "z"

#> FROM "df"But to make it clear that you’re deliberately calling a SQL function,

we recommend using the .sql pronoun:

lf |> transmute(z = .sql$foofify(x, y))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT foofify("x", "y") AS "z"

#> FROM "df"If you’re working inside a package, this also makes it easier to

avoid R CMD CHECK notes. Just import .sql from

dbplyr using a roxygen2 tag like

@importFrom dbplyr .sql

Infix functions

As well as prefix functions (where the name of the function comes

before the arguments), dbplyr also translates infix functions. That

allows you to use expressions like LIKE, which does a

limited form of pattern matching:

lf |> filter(x %LIKE% "%foo%")

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *

#> FROM "df"

#> WHERE ("x" LIKE '%foo%')You can also use str_like() for this common case:

lf |> filter(str_like(x, "%foo%"))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *

#> FROM "df"

#> WHERE ("x" LIKE '%foo%')You could use %||% for string concatenation, but in most

cases it’s more R-like to use paste() or

paste0():

Special forms

SQL functions tend to have a greater variety of syntax than R. That

means there are a number of expressions that can’t be translated

directly from R code. To insert these in your own queries, you can use

literal SQL inside sql():

lf |> transmute(z = sql("x!"))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT x! AS "z"

#> FROM "df"

lf |> transmute(z = x == sql("ANY VALUES(1, 2, 3)"))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT "x" = ANY VALUES(1, 2, 3) AS "z"

#> FROM "df"This gives you a lot of freedom to generate the SQL you need:

Window functions

Things get a little trickier with window functions, because SQL’s

window functions are considerably more expressive than the specific

variants provided by base R or dplyr. They have the form

[expression] OVER ([partition clause] [order clause] [frame_clause]):

-

The expression is a combination of variable names and window functions. Support for window functions varies from database to database, but most support:

- ranking:

row_number(),min_rank(),rank(),dense_rank(),percent_rank(),cume_dist(),ntile(); - offsets:

lead(),lag(),first(),last(),nth(); - aggregates:

mean(),sum(),min(),max(),n(),n_distinct(); - cumulative:

cummean(),cumsum(),cummin(),cummax().

- ranking:

The partition clause specifies how the window function is broken down over groups. It plays an analogous role to

GROUP BYfor aggregate functions, andgroup_by()in dplyr. It is possible for different window functions to be partitioned into different groups, but not all databases support it, and neither does dplyr.The order clause controls the ordering (when it makes a difference). This is important for the ranking functions since it specifies which variables to rank by, but it’s also needed for cumulative functions and lead. Whenever you’re thinking about before and after in SQL, you must always tell it which variable defines the order. If the order clause is missing when needed, some databases fail with an error message while others return non-deterministic results.

-

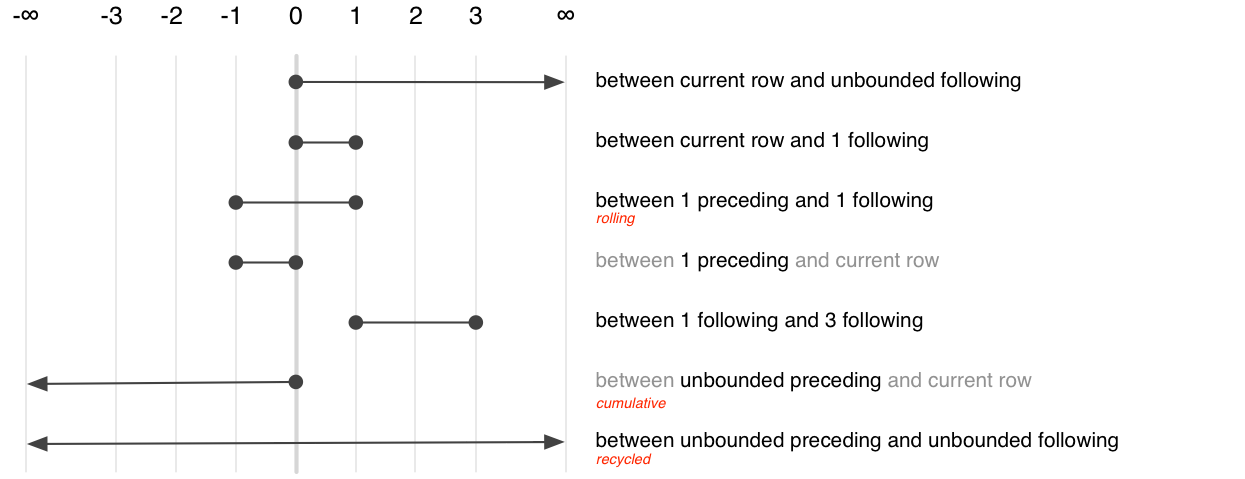

The frame clause defines which rows, or frame, that are passed to the window function, describing which rows (relative to the current row) should be included. The frame clause provides two offsets which determine the start and end of frame. There are three special values: -Inf means to include all preceding rows (in SQL, “unbounded preceding”), 0 means the current row (“current row”), and Inf means all following rows (“unbounded following”). The complete set of options is comprehensive, but fairly confusing, and is summarised visually below.

Of the many possible specifications, only three are commonly used. They select between aggregation variants:

Recycled:

BETWEEN UNBOUND PRECEDING AND UNBOUND FOLLOWINGCumulative:

BETWEEN UNBOUND PRECEDING AND CURRENT ROWRolling:

BETWEEN 2 PRECEDING AND 2 FOLLOWING

dbplyr generates the frame clause based on whether you’re using a recycled aggregate or a cumulative aggregate.

To see how individual window functions are translated to SQL, we can

use transmute():

lf <- lazy_frame(g = 1, year = 2020, id = 3, con = simulate_dbi())

lf |> transmute(

mean = mean(g),

rank = min_rank(g),

cumsum = cumsum(g),

lag = lag(g)

)

#> Warning: Windowed expression `SUM("g")` does not have explicit order.

#> ℹ Please use `arrange()`, `window_order()`, or `.order` to make

#> deterministic.

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT

#> AVG("g") OVER () AS "mean",

#> CASE

#> WHEN (NOT(("g" IS NULL))) THEN RANK() OVER (PARTITION BY (CASE WHEN (("g" IS NULL)) THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) ORDER BY "g")

#> END AS "rank",

#> SUM("g") OVER (ROWS UNBOUNDED PRECEDING) AS "cumsum",

#> LAG("g", 1, NULL) OVER () AS "lag"

#> FROM "df"If the lazy frame has been grouped or arranged previously in the pipeline, then dbplyr will use that information to set the “partition by” and “order by” clauses:

lf |> arrange(year) |> mutate(z = cummean(g))

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *, AVG("g") OVER (ORDER BY "year" ROWS UNBOUNDED PRECEDING) AS "z"

#> FROM "df"

#> ORDER BY "year"

lf |> group_by(id) |> mutate(z = rank())

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT *, RANK() OVER (PARTITION BY "id") AS "z"

#> FROM "df"There are some challenges when translating window functions between R and SQL, because dbplyr tries to keep the window functions as similar as possible to both the existing R analogues and to the SQL functions. This means that there are three ways to control the order clause depending on which window function you’re using:

For ranking functions, the ordering variable is the first argument:

rank(x),ntile(y, 2). If omitted orNULL, will use the default ordering associated with the tbl (as set byarrange()).Accumulating aggregates only take a single argument (the vector to aggregate). To control ordering, use

order_by().Aggregates implemented in dplyr (

lead(),lag(),nth(),first(),last()) have anorder_byargument. Supply it to override the default ordering.

The three options are illustrated in the snippet below:

lf |> transmute(

x1 = min_rank(g),

x2 = order_by(year, cumsum(g)),

x3 = lead(g, order_by = year)

)

#> <SQL>

#> SELECT

#> CASE

#> WHEN (NOT(("g" IS NULL))) THEN RANK() OVER (PARTITION BY (CASE WHEN (("g" IS NULL)) THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) ORDER BY "g")

#> END AS "x1",

#> SUM("g") OVER (ORDER BY "year" ROWS UNBOUNDED PRECEDING) AS "x2",

#> LEAD("g", 1, NULL) OVER (ORDER BY "year") AS "x3"

#> FROM "df"Currently there is no way to order by multiple variables, except by

setting the default ordering with arrange(). This will be

added in a future release.